Healthy-branded foods now fill U.S. grocery aisles—from organic deli slices to low-fat yogurts and zero-sugar snacks.

Labels like “organic,” “natural,” and “low sugar” make foods seem healthy, and many shoppers buy them with good intentions. But nutrition researchers warn that current labeling rules don’t always lead people to the healthiest choices.

Lax rules on front-of-package labels let food manufacturers make broad, sometimes misleading marketing claims. These claims can hide how the product is made—and how little its nutritional value matches its “healthy” branding.

In this article, we look at how foods marketed as “healthy” often fall into the ultra-processed category, and why that matters for anyone trying to make informed food choices.

How food labels can hide ultra-processed ingredients

Food companies can get away with using misleading labels because of legal loopholes.

The term ultra-processed food (UPF) doesn’t have an official federal definition. It comes from public-health research, not food regulations, so it’s not part of formal labeling rules.

In July 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began public research into the matter. But no rules have been proposed so far.

That means manufacturers can still use FDA-approved labels such as “organic” or “healthy” on ultra-processed foods, as long as they meet a few minimal requirements.

Here’s what food labels actually tell you—and what they often leave out.

“Organic” seals and labels

The “organic” label was introduced back in 1990 under the National Organic Food Production Act. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) then created a certification program and an official “organic” label that producers can use.

What the “organic” label means

The food product with this label was certified as produced without certain prohibited methods like genetic engineering or ionizing radiation, and without specific substances, such as synthetic growth hormones or routine antibiotics.

Organic doesn’t mean chemical-free. Pesticides and other pest-control treatments are still allowed. This means an organic potato might be grown almost the same way as a conventional one.

Research from Stanford University’s Center for Health Policy found that organic-labeled produce, on average, is no more nutritious than regular fruits and vegetables. It’s also just as likely to contain trace amounts of bacteria such as E. coli or Salmonella, which can cause stomach upset.

What “organic” doesn’t confer

Organic doesn’t mean healthy. Organic foods can still be highly processed and have low nutritional value.

High sugar content in products like cereal bars or yogurt cups—whether organic or not—is still a concern. Sodium (salt) can also be organic, yet it’s often present in large amounts in frozen meals and other packaged foods.

Packaged foods made with organic ingredients may still contain many additives.

Manufacturers can label products as “Made with [specific organic ingredient]” if at least 70% of the ingredients are organic. The remaining 30% can include non-organic and synthetic substances, such as artificial flavors or preservatives.

“Natural” and “100% natural”

Unlike “organic”, the “natural” label doesn’t have precise usage criteria from regulatory agencies like the FDA or the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The USDA and the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) only set standards for meat, eggs, and dairy.

For most processed goods, the “natural” label can be used very loosely, which leaves shoppers guessing.

What “natural” label means

The FDA recommends using this label for foods that “do not contain added color, artificial flavors, or synthetic substances.” But this is just a guideline— not an enforced rule.

What “natural” doesn’t confer

Just because something says “natural” doesn’t make it healthy.

Packaged goods with the “natural” label, like charcuterie, juices, protein supplements, or prepared meals, may still include ingredients grown with pesticides, or GMOs, or be loaded with natural sweeteners like fructose, sucrose, stevia, or agave nectar.

Manufacturers can also use the “natural” label for highly processed foods if they include lab-made versions of natural additives. Some common examples of lab-made, but natural-sounding ingredients, are:

- Erythritol: an industrial sugar alcohol, often used as a low-calorie sweetener.

- Refined starches: made from grains, but stripped of fiber, vitamins, and minerals; they have a high-glycemic index.

- Maltodextrin: an ultra-refined, lab-made starch. It may sound like a natural and beneficial ingredient, but in reality, it causes a sharp spike in blood sugar.

Finally, “natural” says nothing about how the food was processed. Such products can still undergo heavy cooking or smoking, and meats labelled “natural” that are cooked at high temperatures may produce potentially cancerogenic substances released during the process.

“Low-sugar,” “low-fat,” “low-sodium”

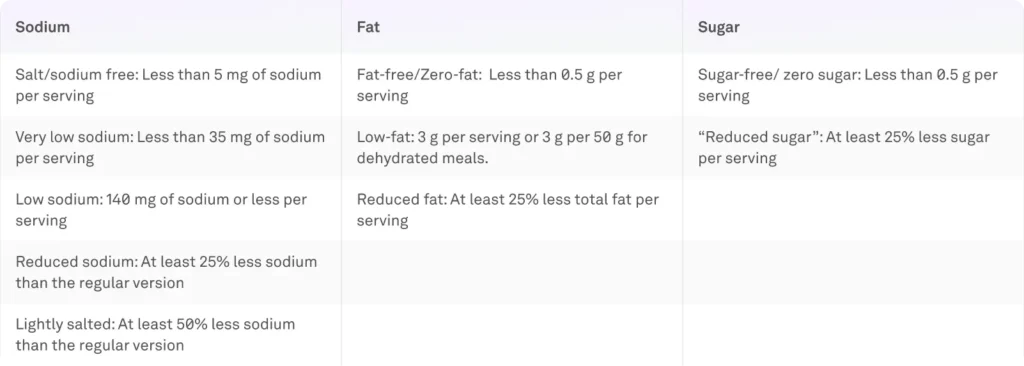

Unlike vague labels like “natural,” nutrient claims such as “low-sugar,” “low-fat,” or “low-sodium” are regulated by the FDA. To use these labels, manufacturers must comply with specific guidelines on the amount of each nutrient that may be in the product.

What these labels mean

A “low” or “reduced” claim indicates that the nutrient is present in smaller amounts—but it doesn’t mean the product is completely free of sugar, fat, or salt.

Sources: FDA, CustomsMobile, Legal Information Institute

What these labels don’t confer

“Low-sugar,” “low-fat,” and “low-sodium” labels only tell you about the amount of certain nutrients—they don’t reveal how processed a food is or what other ingredients it contains.

For example, a “no sugar” or “low-sugar” processed food may still include sugar substitutes, sugar alcohols, or non-nutritive sweeteners. A “low-sugar” yogurt may contribute more glucose than expected, and still contain highly processed ingredients like gums, starches, and lab-made flavors.

These claims are also based on recommended food portion sizes, known as the Reference Amount Customarily Consumed (RACC), and these don’t always match how people actually eat. Nutrition facts may be listed for a single spoon of peanut butter, even though people often use a much larger amount.

“Plant-based”

The FDA developed guidelines on what can (and cannot) be labeled “plant-based” as an alternative to animal-origin foods. However, since these are only recommendations and not official laws, food companies can interpret the rules quite loosely.

What a “plant-based” label means

The only real meaning is that the product doesn’t have any animal-derived ingredients (hopefully) and uses one or more plant sources.

Under FDA guidance, the primary plant type—like soy—should be included in the product name (for example, “soy burger patties”), and all plant ingredients should appear on the ingredient list.

What “plant-based” label doesn’t confer

A “plant-based” label doesn’t mean that food is healthier or less processed.

Many well-known plant-based foods—burgers, nuggets, sausages, deli slices, and dairy alternatives—are considered ultra-processed. Some of them are on the list of the worst ultra-processed foods in the American diet. To make them taste and feel familiar, manufacturers use large amounts of additives, such as synthetic protein isolates and concentrates, industrial oils, starches, gums, and various flavor enhancers.

In other words, just because a food comes from plants doesn’t mean it’s close to nature.

“Healthy”

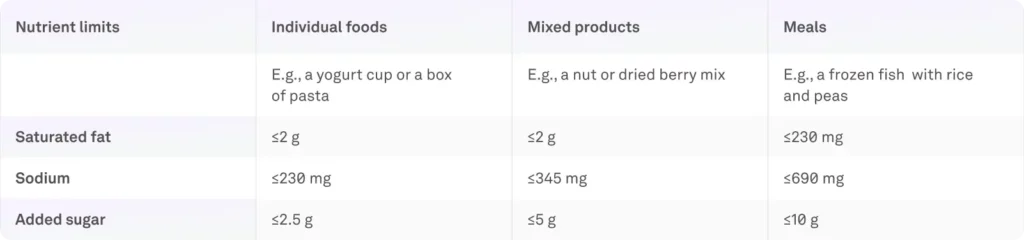

Out of all food labels, the “healthy” carries the most weight—thanks to the updated FDA rule. Only nutrient-dense foods with no added ingredients (except water) can qualify for this label.

What the “healthy” label means

To use the “healthy” label, foods must stay under specific limits for saturated fat, sodium, and added sugar. The limits vary depending on the type of food.

Source: FDA

What the “healthy” label doesn’t confer

A “healthy” label says nothing about processing or artificial ingredients.

The rule is voluntary—manufacturers aren’t required to use it, and many products that meet (or don’t meet) the criteria may still use vague health claims.

The rule also doesn’t regulate other aspects of food processing, such as the use of refined grains, industrial additives, ultra-refined starches, sugar alcohols, or artificial sweeteners, emulsifiers, and flavor enhancers. That means some UPFs could technically meet the nutrient thresholds and still carry a “healthy” label.

Also, high-intensity sweeteners (non-caloric sugar substitutes) are not counted as added sugars under the rule. This regulatory gap allows manufacturers to use them to bypass sugar limits. A product can still qualify as “healthy” on paper, even if it contains a high amount of artificial sweeteners.

Six common ultra-processed foods marketed as “healthy”

To show you just how misleading front labels can be, we examined several popular products from U.S. stores:

- Organic “no stir” peanut spreads

- “Healthy” protein bars

- Organic granola or “whole grain” cereal

- Plant-based milks

- “Fresh” deli slices and sausages

- Low-fat or high-protein yogurt cups

On the front, all of these pretend to be “healthy” and “organic” choices. But on closer inspection, their nutritional value may be lower than expected, and their ingredient list shows they are often just as processed as their regular counterparts.

Let’s review them one by one.

1. Organic “no stir” peanut spreads

Source: Walmart

A peanut butter made from just roasted, unsalted nuts can be a nutritious snack. But the “spread” versions often aren’t because of the added emulsifiers and stabilizers.

Organic MaraNather Peanut Butter Spread bears a USDA Organic label and bold claims like “no sugar or salt added.” But the ingredient list tells a fuller story: it includes organic palm oil, added to keep the texture smooth and spreadable.

Palm oil, whether organic or not, is high in saturated fat. A diet high in saturated fat is associated with increased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), often called “bad cholesterol.”

Pro tip: When a peanut butter advertises itself as “no-stir,” it’s usually because added oils or stabilizers are preventing natural oil separation.

2. “Healthy” protein bars

Source: Target

Protein bars are often marketed as a good source of clean energy or natural proteins. But the ingredient list isn’t always as “healthy” as we’re led to believe.

The nutritional base of Pure Protein Chocolate Deluxe Bar is processed proteins (whey/milk/soy protein isolates). These provide a different nutritional profile than whole-food protein sources.

Processed protein isolates are stripped from their original food “matrix,” meaning they come without the fiber, fats, and micronutrients naturally found in whole foods. As a result, they’re absorbed differently, tend to be less satiating, and don’t offer the same overall nutritional benefits as minimally processed protein sources like dairy, eggs, nuts, or legumes.

The bar also contains maltitol syrup—a commercially produced, refined sweetener. Although it has a lower glycemic index than regular sugar, it can still raise blood sugar and insulin levels.

Other highly processed ingredients include refined tapioca starch, modified palm oil, and various flavor enhancers.

Given that profile, Pure Protein bars—and many similar products from popular brands like Clif, KIND, and Quest—qualify as ultra-processed food.

A closer look at the ingredient list reveals refined fibers and fiber substitutes, sugar alcohols, glycerin, cocoa butter, and emulsifiers—a familiar lineup in highly processed foods.

3. Organic granola or “whole grain” cereal

Source: Kashi

Granolas and whole-grain cereals are often marketed as a “healthy” breakfast staple. Although many start with organic grains, much of the whole-grain structure and nutrients can be lost during processing.

The Original Kashi GO® Protein & Fiber Cereal carries a non-GMO verified label and highlights its high protein and fiber content on the front of the box.

A closer look at the ingredient list tells a different story. Along with whole grains, it includes soy protein concentrate, a common ultra-processed component. The packaging mentions “natural flavor”, which is essentially a code name for artificial flavoring.

Other cereal brands go big on added sugars, whether from natural sources or artificial sweeteners. A single serving of QUAKER® Simply Granola Oats with Honey & Almonds contains over 13 grams of sugar—about 2.5 grams above the FDA limit for a “healthy” label.

4. Plant-based milks

Source: Target

Plant-based milks share few nutritional characteristics with the plants they’re made of. Multiple processing steps—including filtering and protein modification—can significantly change the final product, even when the base plant is organically grown.

Did you know? 90.1% of plant-based beverages and 95% of almond milks in the USDA Branded Food Product Database meet the criteria for being ultra-processed.

Most plant-based beverages contain high levels of additives, such as sugars, gums, seed oils, and stabilizers, to improve taste and extend shelf life.

To get its creamy texture, Oatly uses additives such as low-erucic acid rapeseed oil (an industrial ingredient) and dipotassium phosphate (an emulsifier/stabilizer).

5. “Fresh” deli slices and sausages

Source: Walmart

“Natural” sausages and deli meats may sound wholesome, but processed meat products are often among the least healthy UPFs. To keep the products fresh and flavorful, manufacturers add extra industrial ingredients like emulsifiers, sweeteners, and colorants.

For example, Oscar Mayer Deli Fresh Oven Roasted Turkey Breast includes:

- Modified cornstarch — a thickening and binding agent

- Cultured dextrose — a sugar-based preservative

- Sodium phosphates — salt-based additives for improving shelf life

- Carrageenan — a thickener and stabilizer

It also contains regular sugar and caramel color—ingredients that typically don’t belong in meat.

Even cleaner-positioned options such as Applegate Naturals Chicken & Maple Breakfast Sausages contain added sugars— like cane sugar and maple syrup. So, despite claims like “natural” or “fresh,” these products may be less nutritious than they appear to be.

6. Low-fat or high-protein yogurt cups

Source: Light + Fit

Health-halo packaging on many yogurts makes them seem undeniably good for our health. Yet, “low-fat” and “high-protein” options are often among the most processed.

Their base—cultured pasteurized ultra-filtered nonfat milk—has already gone through multiple processing steps. Water and lactose are moved, protein and calcium are concentrated, and the milk is fermented to mimic the texture of a natural yogurt.

By the time it reaches the cup, it bears little resemblance to a simple dairy product.

All the add-ins make these yogurts even more processed. For example, Light + Fit Greek Nonfat Yogurt includes:

- Fructose — extra sugar added on top of milk’s natural sugars

- Sucralose — an artificial sweetener, linked to changes in gut health and insulin levels

- Natural flavorings — industrial flavor compounds used to create a consistent taste.

Other low-fat yogurt cups often include thickeners, stabilizers, sugar substitutes, and flavor enhancers. So even though these yogurts may seem natural, they’re, in fact, highly processed.

How health-framed UPFs can undermine your wellness goals

When UPFs are wrapped in healthy branding, it’s easy to believe they’re a good choice. Yet, beyond the comforting claims on the box, our bodies remain sensitive to the mix of additives, sugars, and engineered flavors inside.

Here’s why healthy-branded UPFs deserve extra scrutiny:

- Blood sugar spikes. Many “organic” and “natural” breakfast foods and snacks are loaded with added refined sugars and syrups. These are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream, causing sharp spikes in blood glucose and insulin levels.

- Additives linked to inflammation. Emulsifiers such as polysorbate-80, carboxymethylcellulose, carrageenan, and mono- and diglycerides improve product texture, but may irritate the gut lining, increase inflammation, and affect digestion, as studies have shown.

- Hidden calories and overeating triggers. Healthy-branded UPFs are engineered to be highly appealing, making it easy to eat more than intended. Over time, this can lead to weight gain and disrupt metabolic health.

- Engineered proteins. Many products labeled as “high-protein” rely on whey, soy, or pea protein isolates rather than whole-food protein sources. Isolates provide lower nutritional value and lack essential fats, minerals, and amino acids.

- Flavor enhancers. Added “natural flavors” and sweeteners train the palate to expect more intense tastes. As a result, whole foods may seem tasteless by comparison, making healthy, mindful eating feel like a struggle.

In short, health-focused branding is only a surface. Only the ingredient list gives the full, unfiltered picture showing what’s really inside.

How to spot UPFs among “healthy” or “organic” goods

The golden rule: start with the ingredients label. Focus on these three red flags.

- Ingredients that don’t sound familiar. If it’s not something you’d use in your own kitchen, it’s likely an industrial ingredient. Protein isolates, starches, and emulsifiers are all signs of heavy processing.

- Added sugars. Even natural-sounding ingredients like organic cane sugar or agave syrup, let alone lab-sounding ones such as maltodextrin, have no place in a healthy diet.

- Added oils. If the food naturally doesn’t need oil (like oat milk), it shouldn’t appear on the ingredients list.

Learn how to recognize ultra-processed foods on the shelf.

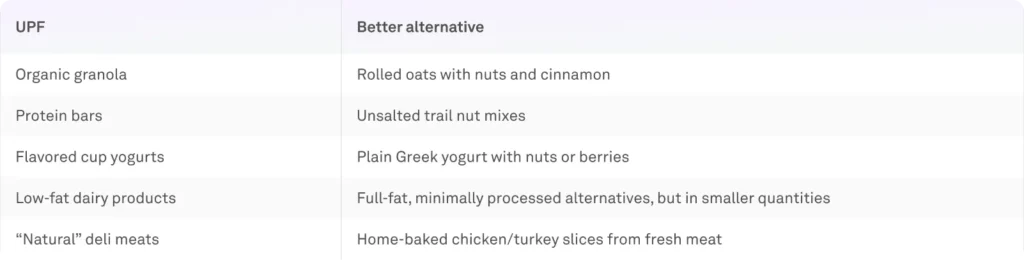

A few simple changes for a more balanced diet

Eating well doesn’t require complicated recipes or hours in the kitchen.

Swapping a few “healthy-sounding” UPFs for homemade alternatives improves energy levels and overall well-being. Here are several simple swaps to start with.

This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Individual nutritional needs vary. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance.